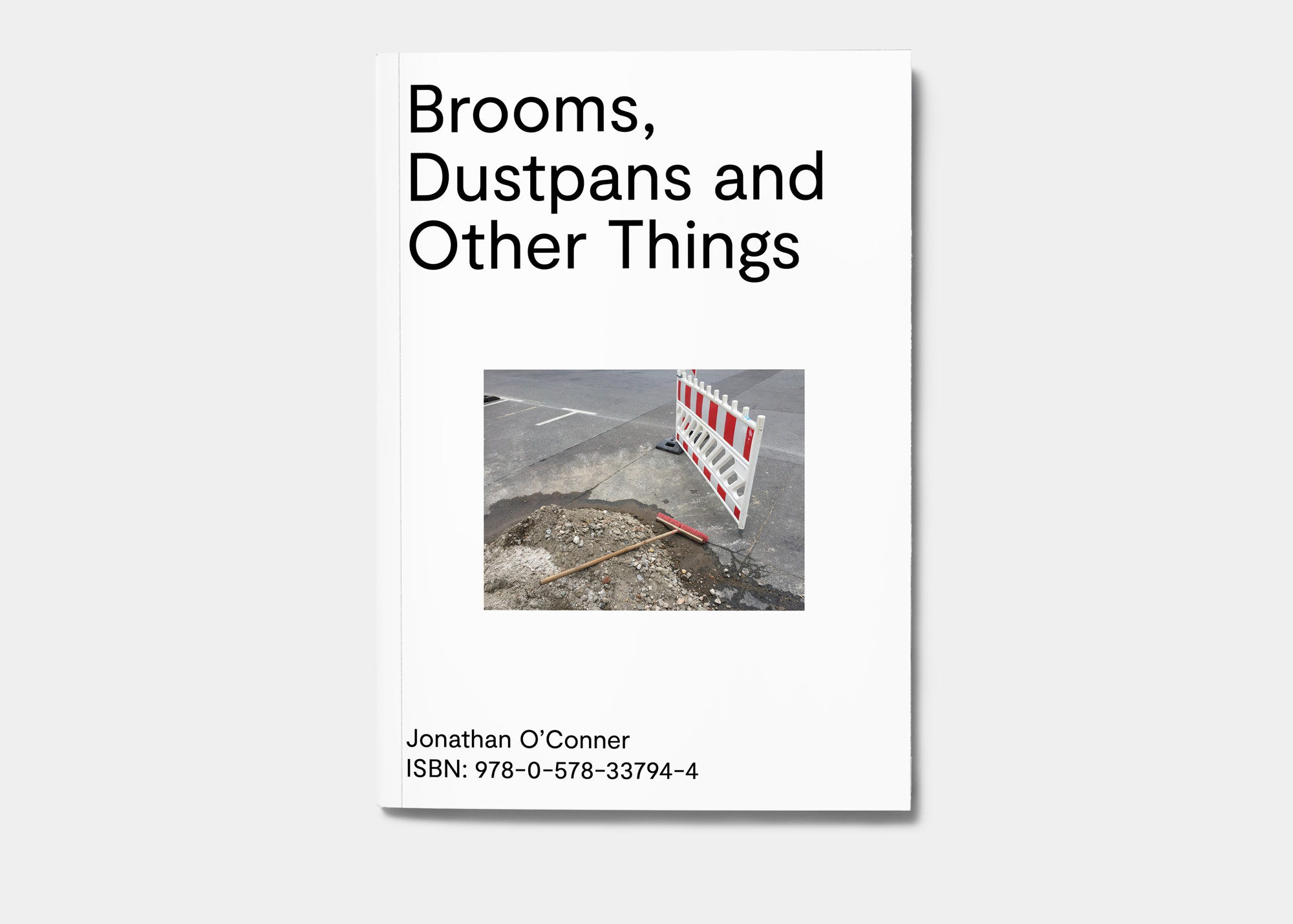

Our world is decaying. I’m not speaking metaphorically—even if our social systems are worn, our supply chains are fracturing, and our climate is compromised. Literally, the structures and objects around us are actively decomposing.

It’s a truth that has always been. Mountains become boulders, boulders become stones, stones become pebbles, pebbles become sand. All matter—natural and synthetic—is bound by the same fate. While some materials are quicker to break down than others, everything that we’ve ever touched will, at some point, disintegrate into fine particulate.

How do we live with such a fact? Some find solace in religion. Some live happily unaware. Others actively ignore. How we choose to engage with material decay speaks volumes. It’s not only a matter of philosophy or theology. It determines how we care for our planet: how we extract, manipulate, consume, and discard the physical matter around us. It’s worth arguing that a person’s relationship with decay is motivated by their attitudes toward maintenance. An awareness comes from tending to objects and the bits discharged along the way. Acceptance develops through routine, knowing that deterioration is unending.

I have no memory of sweeping for the first time. Like other skills learned at a young age, it now feels like something that I’ve always known how to do. I’m sure there was a clean-up themed song involved encouraging all the kindergarteners in my class to do their part. Or maybe it was something I learned while imitating my parents around the house. Regardless, the idea that cleaning is essential in life—and more or less unavoidable—was nurtured early on.

If there’s one thing we share, it’s our capacity to make a mess. Our bodies continuously shed hair and skin. We’re prone to drop things that spill and shatter. Our tires cast dirt, wherever we go. The certainty of debris looms heavy over us all. That’s not to mention the pollen, minerals, and other organic stuff continuously settling and stirring about. Simply put: our world is dirty. The proverbs and idioms on the topic tell us that dirtiness is nearly inescapable. Within each are morals guiding us towards purity and self-betterment. To free your life of grime and clutter is serene, noble, god-like.

And yet many of us don’t clean up after ourselves or each other. Long, troubled histories have calcified the idea that those with power are above such inferiority. Cleaning was the hidden toil of servants and slaves. It’s the work of women that’s never done. It’s outsourced and undervalued. Many times, the reward of cleanliness comes with expenses as hidden as the tools themselves—tucked away and out of sight.

The first broom that caught my eye was resting on a black metal fence in a plaza in Old Havana. It was simply a bundle of dry palm leaves bound with cloth and string. Together, the long, rigid stems formed a handle, as the fronds naturally fanned into bristles. With remarkable clarity, its maker had transformed organic waste into a functional object.

But what do they reveal in us? Everyone would sweep in a society free of gender, racial, and economic inequality. Until that day is realized, who’s making brooms and who’s sweeping up? A monk guided by faith and dedication. A neighbor upholding personal pride and local hygiene. A grandmother tending to her garden and her health. An employee bound to a location and a paycheck.

Eventually, our relationship with decay will be unambiguous. We'll all be forced to reconsider our domestic roles and communal duties. We might then realize that sweeping isn’t an act of preservation, but rather a practice in the banal with no end in sight. If we do, it'll be the humble broom that helps us balance determination with acceptance, in a world destined to fall apart.